|

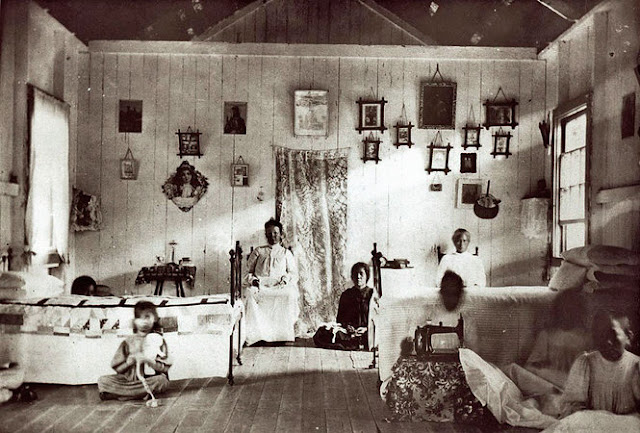

| Bishop Home, via |

Published: 2003

It's about: Rachel Kalama is a happy seven-year-old girl living in Honolulu at the end of the 19th century. But then her mother discovers a numb red sore on Rachel's leg, and there's only so long her family can keep it a secret: their little girl has leprosy, a feared, poorly understood, and shameful disease for which there was no cure or effective treatment. Soon Rachel is removed from her family and shipped off to Kalaupapa, a leper colony on the island of Moloka'i.

On Moloka'i, Rachel grows up and finds life, love, and family (alongside a heaping dose of tragedy) among her fellow exiles and their caretakers. Her life coincides with an eventful period in Hawaii's history; she sees the overthrow of the monarchy, the introduction and boom of tourism, WWII and the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and eventual statehood. Rachel and the islanders get to experience a lot of twentieth-century inventions for the first time: recorded music, moving pictures, airplanes. I loved reading about people's introductions to these and other pieces of modern life.

I thought: This is exactly the kind of novel I love: rich with well-researched historical and cultural details, a tragic and dramatic life story with memorable, complex characters. It even has a medical element to boot! There aren't really heroes and villains, just people struggling along with what they have and making choices based on their selves and their circumstances. I should probably mention that I lived in Hawaii when I was in high school, and so the setting and trappings of Moloka'i have some special significance for me. I loved that Brennert included lots of Hawaiian words, culture, and mythology. Despite the author being haole, the book feels Hawaiian.

I also thought Alan Brennert did a decent job writing from a woman's perspective. I forgot, sometimes, that Rachel was written by a man, and you really can't say that about some male authors. My only complaint in that department is that all the female characters in Moloka'i seem unusually willing to part with their clothes, including disfigured teens who were raised in a convent and even some of the nuns! This isn't the first time I've read a book by a male author that has a bunch of female characters casually getting naked regularly. The tendency amuses me.

While I'm in complaint mode, I do have a few other things to mention. Brennert's style is smooth and easy to read, but there is some slight cheesiness now and again. I can tell that he is a screenwriter and OH how I wish some studio would pick up Moloka'i and make it into a miniseries. Brennert's prose isn't high art, but it is capable enough to bring out his real strengths: storytelling and character development. I really would have appreciated a more detailed map of Moloka'i than the one printed in the front of the book, and a glossary of Hawaiian terms and some pronunciation guidelines would have been nice. My memories from 11th grade Modern History of Hawaii class are pretty fuzzy and I had to turn to google for clarifications.

Moloka'i may not be timeless great literature, but it's a full, beautiful story grounded in fact, with lots of Big Ideas to chew on: freedom and exile, forced exile/imprisonment and self-exile, parent-child relationships within and without biological ties, faith in the face of tragedy. This book is going to stick with me, and it was just the thing to get me out of my post-Anna Karenina rut. You can bet I'll be reading Alan Brennert's other Hawaii book, Honolulu.

Verdict: Stick it on the shelf!

|

| Kalaupapa today, via (note the pali, cliffs that isolated the settlement from the rest of the island) |

(And if you like this setting, be sure to check out the movie Princess Kaiulani.)

Warnings: A little fairly-descriptive sex, one brief but graphic scene of domestic violence, some swears.

Favorite excerpts: "Grief and anger doesn't shock me." Catherine paused. "Rachel, do you remember the day at the convent when we saw the old biplane? Remember what I said?"

Rachel laughed without amusement. "I don't even remember what I said."

"'Who can doubt the presence of God in the sight of men whom he has given wings.' I recall that so precisely because I've had time to consider my error." She smiled. "God didn't give man wings; He gave him the brain and the spirit to give himself wings. Just as He gave us the capacity to laugh when we hurt, or to struggle on when we feel like giving up.

"I've come to believe that how we choose to live with pain, or injustice, of death... is the true measure of the Divine within us. Some, like Crossen, choose to do harm to themselves and others. Others, like Kenji, bear up under their pain and help others to bear it.

"I used to wonder, why did God give children leprosy? Now I believe: God doesn't give anyone leprosy. He gives us, if we choose to use it, the spirit to live with leprosy, and with the imminence of death. Because it is in our own mortality that we are most Divine."

What I'm reading next: The Other Side of Normal by Jordan Smoller