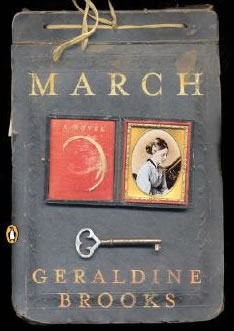

Published: 2005

It's about: March, the 2006 Pulizter Prize winner by Geraldine Brooks, follows Mr. March, the father from Little Women (my review here), through his experience serving as a chaplain (religious leader) in the Civil War. The second chapter flashes back 20 years earlier. Mr. March works as a traveling salesmen in the south, where he meets a young slave woman named Grace and has a traumatic experience. During the war, he meets her again when the plantation house where he met her years before has been transformed to an army "hospital," where she nurses the dying soldiers. Secrets from the past come to light, and March learns of the consequences to some of his actions. (Ambiguity = no spoilers.)

Within the next few months, March goes on to help former slaves by teaching them to read and getting them new clothes. I'll just say that things once again begin to go awry and lots of people die. March is gravely wounded and racked with guilt. His wife, (yes that would be Marmee,) comes to visit him in the hospital. As she's there, March's story slowly unfolds to her, and their relationship is changed forever.

I thought:

The first thing that stood out to me and perhaps the thing I most loved about this book is its complexity. We're pretty much getting the whole story here with all the gory details. March isn't the bright, shining exemplar that you would think he would be from reading Little Women. For that matter, Marmee has a lot of issues too. People are naturally complex, with battling emotions and radical opinions, and for this reason Brooks' characters were very strong.

There was a lot of violence in this book. Yes, in some parts even bordering Blood Meridian intensity. For example, one of the first battle scenes has March notice a vulture eating a dead soldier with organs hanging out of its beak. The violence was intense but I felt like it had a strong place in this novel and was there for a reason - to show how terrible the Civil War really was, and to help place March's character within that context.

The narrative itself was SUPER intense as well, in the most shocking and best of ways. There are a few scenes in here that felt like a punch in the stomach. There is a strong focus on race issues and slavery. I'm definitely a fan of Toni Morrison but I think in some ways I prefer Brooks' approach to slavery. Neither Morrison nor Brooks take a black and white approach (no pun intended ...), ie, black people/abolitionists = good guys, white slave owners = bad guys. It's a lot more complex of an issue than that. I feel like Morison takes a more poetic, ambiguous approach and Brooks takes a more narrative-fueled, blunt approach.

Also, as she explains in the Afterward, Geraldine Brooks did extensive research into Louisa May Alcott's father, Bronson Alcott, to use as the basis for March's character. Little Women was, of course, based on Alcott's childhood and the father was originally based on her own father, although he never fought in the Civil War. Her writing style is very clearly influenced by the "voice" of that time, which fits perfectly.

Needless to say, March was very different from Little Women and I liked it much better. But then again, I love war books. I'll take Catch-22 over Pride and Prejudice in a heartbeat.

Verdict: This one is going right on the shelf.

Reading Recommendations: You don't have to have read Little Women to appreciate this book, but it's helpful to be familiar with the story. I would recommend at least watching the 1994 film adaptation before reading this book.

Warnings: Graphic violence. Disturbing themes.

Favorite excerpts:

Are there any two words in all of the English language more closely twinned than courage and cowardice? I do not think there is a man alive who will not yearn to possess the former and dread to be accused of the latter. One is held to be the apogee of man's character, the other its nadir. And yet, to me, the two sit side by side on the circle of life, removed from each other by the merest degree of arc.