|

| via |

Reviewed by Ingrid

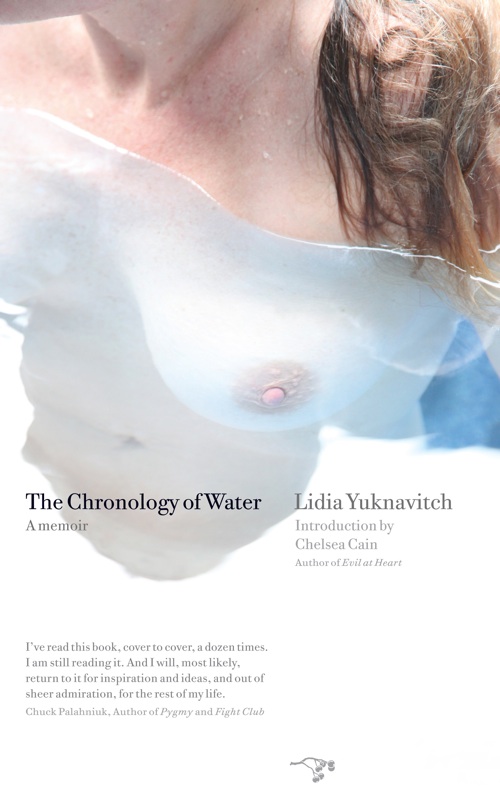

Published: 2011

It's about: This is a tough one to summarize. Here's the goodreads description:

"This is not your mother’s memoir. In The Chronology of Water, Lidia Yuknavitch expertly moves the reader through issues of gender, sexuality, violence, and the family from the point of view of a lifelong swimmer turned artist. In writing that explores the nature of memoir itself, her story traces the effect of extreme grief on a young woman’s developing sexuality that some define as untraditional because of her attraction to both men and women. Her emergence as a writer evolves at the same time and takes the narrator on a journey of addiction, self-destruction, and ultimately survival that finally comes in the shape of love and motherhood."

I thought: Cheryl Strayed called this book "a brutal beauty bomb and a true love song." I like that description. This book is brutal and sometimes difficult to digest, but it is beautiful. I was stunned by Yuknavitch's writing - I read almost the whole thing sitting on my bed in the same position. I reveled in it. I read and reread sentences and paragraphs that impressed me. I laughed at Yuknavitch's clever and funny chapter titles. I dog-eared pages I liked even though the copy I was reading was from the library. I absolutely DIED over this book, I loved it so much. I told Derik that, hands-down, this is the best book I've read all year and perhaps one of the best books I've read, ever.

|

| a still of Yuknavitch from the book trailer |

Yuknavitch's writing breaks down all these barriers. Her narrative flows in many directions without losing its center and its force. Like the nature of water, her writing style is flowing, moving, all encompassing. It is heartbreakingly honest and mindbendingly beautiful. My edition contained a short interview with Lidia Yuknavitch that gave me some great insight into her writing. She talks about bodies - "I think bodes are the coolest thing in ... ever. Your body, Mine. All the different kinds. What glory bodies are" - and how she tries to bring language closer to corporeal experience - "To bring langauge close to the intensity of eperiences like love or death or grief or pain is to push on the affect of language ... I want you to hear how it feels to be me inside a sentence." This is what I think makes Yuknavitch stand apart.

And speaking of bodies .. yes, that is a boob on the cover. The book is sold in stores with a charcoal band around the front covering the boob. I chose to show you the real cover, though, because I think the human body should more often be seen as something beautiful without having to be sexualized. Yuknavitch wrote about the image on the cover here.

And speaking of bodies .. yes, that is a boob on the cover. The book is sold in stores with a charcoal band around the front covering the boob. I chose to show you the real cover, though, because I think the human body should more often be seen as something beautiful without having to be sexualized. Yuknavitch wrote about the image on the cover here.Verdict: Stick it on the shelf. This is by far my favorite book I've read this year.

Warnings: There is a lot of rough language and content in this book. I would not recommend it to everyone. In fact, because of the content I would recommend it to very few. If it sounds like something you would like, I would suggest flipping through and reading a few pages at your local bookstore or library and see if it is something that appeals to you.

Favorite excerpts: "I used to watch Miles fall asleep from drinking boob milk late into the night. I'm guessing all mothers do this. But I bet not all mothers were thinking of Shakespearean sentence structures when they watched their babies drunkenly drift into sleep...when I watched Miles go from mother's milk to burp to deep and frothy dream, his body heavy in my lap, the blue-black of night resting on us, I thought of Shakespearean chiasmus. A chiasmus in language is a crisscross structure. A doubling back sentence. A doubling of meaning. My favorite is 'love's fire heats water, water cools not love.'

As a motif, a chiasmus is a world within a world where transformation is possible. In the green world events and actions lose their origins. Like in dreams. Time loses itself. The impossible happens as if it were ordinary. First meanings are undone and remade by second meanings.

I didn't sleep much the first two years in the forest house. Miles, bless his hungry little head, wanted more milk than any man alive. All night. I thought of my mother--and my own unquenchable, milkless mouth. If this boy wanted milk, I would give it to him. Maybe all our lives were being reborn in the forest. ...

The exhaustion of new parents is absurd. Beyond absurd. But I'm not about to get all righteous about that. In fact, it's something else altogether I want to tell you. I think our exhaustion in the green world brought us to our best selves. Listen to this: the first two years of Miles' life? When I was supposed to be depleted? I wrote a novel and seven short stories. Andy wrote a novel and three screenplays. Read that again. How is it that so much writing happened inside the least amount of time or energy?

Green world.

We had no time. We had no energy. We had no money. What we had was making art in the woods. So when Andy turned to me one night over scotches and said 'We should invent a Northwest press that isn't about f-ing old growth and salmon,' and I laughed my ass off, and then said, 'Yeah, we should,' we just...did. Which is how the zenith of our depletion changed into the zenith of our creative production. Andy and me, we had anther child. An unruly literary press, which we named 'Chiasmus.' Turned out, there were lots of writers in the Northwest who were tired of old growth and salmon. Our first publication was an anthology called Northwest Edge: The End of Reality. Because, you know, it was. Everything we were before we were this, utterly transformed.

Shakespeare.

In our forest we gave art to life, and art to life made us."

What I'm reading next: The Rules of Civility by Amor Towles